In the butty system, the buttyman was allocated a ‘stall’ or section of the seam by the colliery manager and employed several boys and men to help him extract the coal. The buttyman was paid a fee by the colliery owner for each ton of coal sent to the surface.

The rate the buttyman received was negotiated with the colliery owner locally by the individual buttyman, with the support of the Forest of Dean Miners Association (FDMA), the trade union representing Forest miners. The rate depended on the conditions at the face, such as the width and quality of the seam.

Most other tasks in the pits were carried out by men or boys employed directly by the owners, often referred to as the company men.

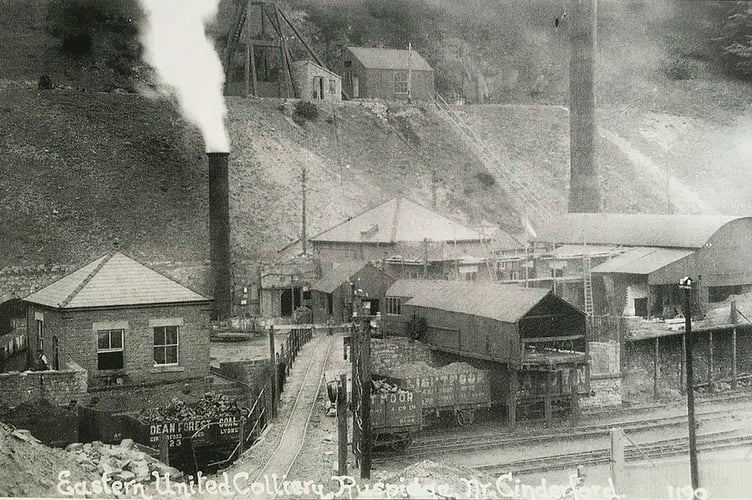

In the Forest of Dean, by the 1920s, most teams consisted of a butty or a pair of butties with one or two day-men and a boy, although the system varied from pit to pit. At Eastern United colliery, near Ruspidge, in the 1920s, the teams varied from four to nine men.

Many Forest buttymen treated their workers well and there would have been a strong sense of loyalty and solidarity within the teams. But it was likely that some buttymen were bullies and exploited their employees and the abuse of teenage boys was the most brutal aspect of the system.

Trade unionism

The butty system created divisions not only between the buttymen and their day-men but also between the buttymen themselves as they competed for the best workplaces or stalls.

Forest buttymen were often active members of the FDMA, who supported them in their conflicts and negotiations with colliery owners.

The buttymen and the colliery owners were obliged to pay the statutory minimum day rate under the 1912 Coal Mines (Minimum Wage) Act for each category of worker, while the buttymen’s earnings were dependent on the tonnage of coal extracted by his team.

Mechanisation

In the late 1920s and 1930s, some mines in the Forest of Dean introduced mechanical coal-cutting to undercut the coal with conveyors to transport the coal from the face. The new equipment was increasingly controlled by underground officials rather than buttymen.

Although mechanisation undermined the butty system its demise appears to have been, at least in part, a result of opposition from within the mining community itself. For ordinary miners, the buttymen had become the managers who kept their pay down.

Eastern United Colliery

Eastern United, was the last Forest colliery still using the butty system in 1938. The pit was owned by Henry Crawshay and Co. which also owned Lightmoor Colliery where the butty system had been abandoned. The workforce at Eastern included 750 men underground and 120 above ground. There were about sixty coal places dug by hand with some180 buttymen.

John Williams, the full-time agent for the FDMA from 1922 to 1953, recalled that at Eastern United:“Not more than a dozen workmen were in the union at this colliery. No workman dared mention the union at this colliery. Most of the Buttymen were undercover agents for the management, and the Managing Director was as tough as they make them.”

Williams and one of the workers at Eastern, Wallace Jones, were keen to bring the system to an end. Jones had built up support among the day-men who worked for the buttymen. He was also the FDMA Executive member for Eastern United and he worked as a miner in various roles for 30 years. In the late 1920s Jones worked himself as a buttyman.

Mass Meeting

At the end of November 1937, Jones and Williams called a public meeting at Cinderford Miners’ Welfare Hall and to their surprise, most of the Eastern United workers, including the buttymen, turned up. David Organ, president of the FDMA, chaired the meeting. Williams explained to the men the reason for calling the meeting:

“I am told there is dissatisfaction at Eastern United Colliery that is extensive and very deep. I am told that one of the causes is the existence of the butty system, and it is significant that the butty men themselves are against it. Many years ago, the system was at least popular among butty men, because they earned big money at the expense, of course, of those who worked for them. Now things have changed, and a process of cutting has been going on so that butty men are getting money that they could earn on a wage basis.”

The meeting agreed that the miners employed at Eastern United Colliery would decide by ballot whether the butty system should be abolished or not. There was not one dissenting vote when the resolution to organise a ballot was put to the meeting.

Dilly-dally methods

The ballot resulted in 336 votes in favour of abolition and 46 for retention. A miners’ deputation supported by Williams then met the owners just before Christmas to discuss the results of the ballot. However, the owners used a series of delaying tactics to obstruct the implementation of the men’s demands. In response, the pit committee at Eastern United asked the FDMA Executive to consider strike action because of the “dilly-dallying methods adopted by the company over this issue.”

A miners’ meeting on Sunday 23 January in St Annals Institute, Cinderford heard Williams express his frustration at the delaying tactics of the management.

Despite the union agreeing to an independent ballot, the directors continued to be obstructive and delay the organisation of the vote. To make matters worse, they sacked Jones and two other workmen. As a result, on Monday 21 February, the Executive Committee of the FDMA decided that the workmen at the colliery should tender notice on Monday 28 February with the view to take strike action the following week.

Coal Owners’ Association

The threat of strike action resulted in the company agreeing to abolish the butty system but the men who had given notice to strike would no longer be employed at Eastern United. The Company offered to find work for them at another of their pits in the Forest. This was not acceptable to the FDMA.

Victory

Negotiations continued until Saturday 5 March when Williams sent a final letter to the management in the hope of averting a stoppage. The owners made a new offer that was deemed to be reasonable. Williams paid tribute to Jones’ contribution to the success of the campaign:

“As a result of his activities in organising opposition to the Butty System, he was sacked. I got him work at another colliery belonging to the same company, and in the meantime, he was appointed Checkweigher at his colliery, and throughout he gave signal service to the union of this district. The credit for this success belongs mainly to Mr Wallace Jones.”

At the Miners’ Welfare Hall on the evening of Saturday 5 March hundreds of miners sat or stood for three hours while Williams detailed the outcome of negotiations. The news that the owners had revised their attitude and that the significant points in the dispute had been settled was received with cheers.

The end of the butty system

The butty system in the Forest survived for over a century, not only because it suited the colliery owners, but because its persistence depended on its acceptance by the mining community.

The loss of any significant differential in wages between buttymen and day-wage hewers was one of the reasons that led to the demise of the butty system. In the end, it was the system itself that became unpopular and it was ex-buttymen such as Wallace Jones with the support of John Williams who helped to finally end a system that only benefitted the colliery owners and their shareholders.

Farewell ol butt!

For a full version of Ian Wright’s article, read the New Regard available from the Forest of Dean Local History Society’s web site and various outlets around the Forest.